Immersive Experience: Sensory Impact and Triggers

In contemporary art, we can trace a distinct direction in which the viewer’s body becomes not only a participant but an element of the environment. If the previous sections focused on the body — its materiality, presence, and phantom forms — here the center shifts: art surrounds, absorbs and envelops the person, transforming perception into a spatial and sensory experience.

Immersive installations act on the level of the body through light, smell, sound, temperature, humidity, and scale, creating an effect of presence and engaging the body’s memory and imagination.

Madre, 2025 — Delcy Morelos

For example, in Madre, Delcy Morelos involves the viewer by introducing a concentrated presence of earth and moisture into the museum space, and the body responds — smells, warmth, and the density of air become an environment in which the familiar distance between the living and the artificial dissolves.

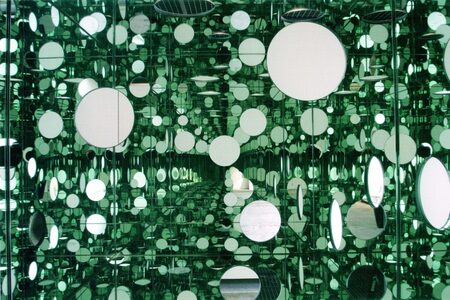

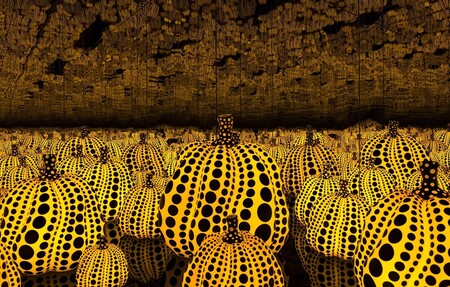

The Passing Winter, 2005 // All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins, 2016 — Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama, by contrast, creates the opposite type of immersion — All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins and The Passing Winter are built on endless optical repetition, where light and reflections dissolve the viewer’s body in an illusory infinity. Here corporeality disappears within a mirrored play, turning into a state of pure visual immersion.

Both artists demonstrate two poles of immersive experience: organic and artificial. In both cases, the viewer finds themselves inside the work rather than in front of it. Both artists construct a sensory landscape using a combination of triggers to activate attention.

This chapter examines four primary sensory triggers that artists use to influence the viewer’s bodily perception: light, smell, sound, and the imitation of touch. These elements function as core sensory media, creating a sense of presence even without physical touch.

Light-Based

Light is one of the simplest and, at the same time, most deceptive means of affecting the body. It leaves no trace, yet changes everything around it: temperature, depth, the sense of time and presence. Light can dissolve space or make it perceptibly dense, almost tactile.

In the works of Olafur Eliasson and Yayoi Kusama, light becomes a bodily experience. It does not merely illuminate — it acts on the viewer physically: it blinds, soothes, disorients, and forces the body to respond. For example, Eliasson creates artificial climatic phenomena — sun, fog, reflections — awakening a memory of natural states and sensations that are absent. Kusama, on the contrary, turns to light as a means of losing boundaries, where the body dissolves in rhythm and reflections.

Here, light is not a source of visibility but a medium of presence. It does not so much show as it is felt, activating bodily memory and producing a phantom sensation of presence.

The weather project, 2003 — Olafur Eliasson

Eliasson’s installation is one of the most illustrative works shaping the concept of immersive perception in contemporary art. The artist created an artificial sun from hundreds of monochromatic lamps and a mirrored ceiling, transforming an industrial space into a simulation of a natural phenomenon.

A paradox emerges: the viewer knows this is an illusion, yet the body responds as if to real sunlight. The pupils contract, the skin senses the warmth of light. Eliasson appeals to sensory reflexes, where a natural experience is reactivated through technological simulation. The viewer is not a spectator but a participant in a collective experience, physically experiencing an artificial natural event.

This work activates a phantom presence of the environment: the viewer senses a sun that does not exist, and air that does not move. Perception deceives the body, and the body — consciousness, producing an effect of slight disorientation and simultaneous calm. Thus, Eliasson explores the boundary between the natural and the artificial, where imitation produces real physiological impact.

Life, 2021 — Olafur Eliasson

Life, 2021 — Olafur Eliasson

In Life, the artist literally dissolves the boundary between the museum and the outside world. The gallery becomes an open ecosystem: water, plants, insects, sounds. All of this becomes part of the exhibition space. Eliasson rejects a visual center, replacing it with processuality — the slow flow of water, the changing of light, the shift of daylight.

The work creates a situation of contemplation: the viewer moves through a space where bodily sensations (humidity, smell, coolness, sound) become part of the perception of art. Here the artificial and the natural converge, forming a new mode of presence — an ecological body responding to its environment.

In this work, the crucial point is the artist’s removal of the traditional distance between artwork and viewer.

Infinity Mirrored Room — Filled with the Brilliance of Life, 2011/2017 — Yayoi Kusama

In Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms, mirrors multiplying the space create a sense of dissolving boundaries between body and environment. Points of light rhythmically blinking in darkness resemble the pulsation of stars, the sensation of infinity.

Unlike Eliasson, where light imitates a natural phenomenon, Kusama places light into environments that produce emotional oversaturation bordering on loss of orientation — a state close to sensory overload. It is an experience of bodily dissociation: a person sees their reflection countless times yet loses the sense of a center, becoming part of a luminous matter.

For Kusama, light is a form of experiencing infinity, where the body ceases to be separate and becomes part of a repetitive rhythm, like a cell within a living organism.

Olfactory

Smell acts bypassing rational perception, directly engaging mechanisms of memory and bodily response. Unlike vision and hearing, it does not require focus — it simply exists, filling space and entering the viewer’s body.

Mike Kelley, Ernesto Neto, and Ade Darmawan use scent as a metaphor for inner experience, collective memory, and history. In their works, smell becomes a carrier of meaning — from traumatic to utopian. It can cleanse, envelop, irritate, or provoke disgust, creating an invisible boundary between artwork and body.

Here, smell is not an addition to the visual but an equal material capable of structuring perception, forming in the viewer a sense of physical presence in the space, even if that space is filled with phantom traces of other bodies.

Deodorized Central Mass with Satellites, 1991-1999 — Mike Kelley

Mike Kelley’s installation is built on the collision of the bodily and the sterile, the living and the artificial. A massive accumulation of worn plush toys is surrounded by ten wall-mounted objects emitting the scent of pine deodorizer. This smell is associated with cleanliness, order, disinfection — with an attempt to suppress the natural smells of life.

Kelley uses scent as a tool that suppresses bodily traces. He effectively deodorizes memory: masking traces of touch, time, warmth. The soft toys — remnants of bodily experience that once absorbed touch and emotion — are turned into a «sterile» sculptural object, where smell serves as a boundary between the living and the artificial.

Here, the smell of cleanliness is unsettling: it does not purify but suppresses, producing a sense of enforced hygiene. The viewer’s body reacts phantomly — feeling an attraction to soft textures while simultaneously rejecting the sterility of the air. A conflict emerges between bodily memory and olfactory repression, in which smell becomes a tool of alienation.

Thus, Kelley examines how sensory memory can be isolated, suppressed, and transformed into artificial nostalgia. His installation evokes not a desire to touch but a sense of the loss of touch.

Léviathan Thot, 2006 — Ernesto Neto

In Ernesto Neto’s work, smell becomes a living material. His giant soft structures made of elastic fabric, filled with spices — turmeric, cloves, cinnamon, pepper — form a pulsating environment where the air becomes dense and scent becomes almost tactile.

The smell is distributed unevenly, as if the structure itself were breathing: the viewer’s body senses varying concentrations of aromas, reacting with relaxation or slight irritation. These shifts turn perception into a bodily process in which the boundaries between viewer and space dissolve.

Neto’s works are often associated with ritual and the collective body. But in the context of sensory exploration, what is essential is that his installations create a feeling of soft interior dwelling, as if the viewer were inside a living organism. Scents establish bodily trust, returning the body to a state of sensorial equilibrium.

Here, phantom tactility emerges not through illusion or image but through distributed presence: the body does not see the source of smell yet senses being inside something alive.

Water Resistanse, 2024 — Ade Darmawan

In his work, the Indonesian artist Ade Darmawan uses scent as a political instrument. The exhibition space is filled with the aromas of jasmine and cinnamon — scents of colonial trade and extractive industries. Through the distillation of essential oils, the artist restores the «bodily memory» of land and history displaced by economic progress.

Here, scent does not produce sensual pleasure — it reveals violence and exploitation hidden behind the aroma of exoticism. The viewer’s body is drawn into a historical field through breathing, becoming a participant in the process of recognition.

Darmawan turns to the idea of breathing as a form of participation: by inhaling air saturated with the scent of herbs and spices, a person literally lets into themselves a history of violence, colonization, and exchange. It is not only a sensory act but an ethical one.

Acoustic

Sound is one of the most delicate ways to affect bodily perception. It forms space even when it is not visible. Acoustic works create an invisible architecture in which the body feels vibrations, density, and direction.

In the projects of Céleste Boursier-Mougenot and Zimoun, sound is born from movement, friction, and rhythm. It is a living, self-organizing process in which physical space becomes an instrument.

Here, sound may soothe, disturb, or evoke the sensation of something «alive.» The viewer does not listen — they are inside the sound, becoming part of the vibrations, part of the body of the installation.

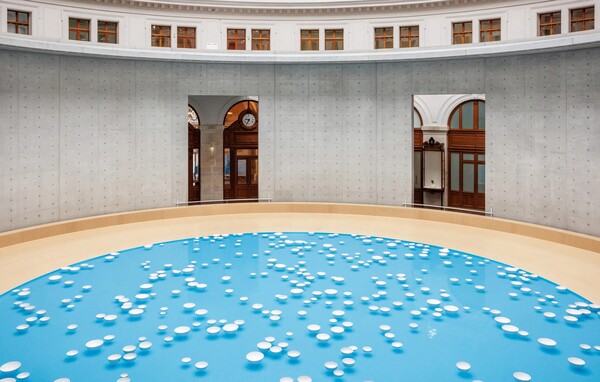

Clinamen, v.10, 2012-2025 — Céleste Boursier-Mougenot

In Boursier-Mougenot’s work, sound becomes living matter generated from the accidental movements of water and porcelain. In bowls floating across the surface of a pool, currents of air, the viewers’ movements, and the space’s vibrations collide. Every strike, every tone is unrepeatable.

Sound does not exist separately from the body. It is formed by micro-movements of air produced by footsteps and the slightest shifts. The viewer becomes an invisible participant in the sonic process, creating sound through their presence.

This work explores the threshold of audibility, where sound becomes vibration and vibration becomes sensation. The body responds not only with the ear but with the skin and internal rhythms. The result is a state of «quiet immersion»: the viewer loses the sense of boundary between self and space, entering the rhythm of water and porcelain. This can be compared to the experience of Tibetan singing bowl meditation.

Museum Haus Konstruktiv Zürich, 2021 // Museum of Contemporary Art MAC Santiago de Chile, 2019 — Zimoun

In his sound installations, Zimoun creates an architecture of noise. His constructions — hundreds of identical mechanisms: motors, strings, cardboard, metal springs, sticks — generate endless micro-sounds as they collide, vibrate, and rattle. Here, sonic monotony forms a rhythm rather than a melody, reminiscent of rain.

As in Boursier-Mougenot’s works, the viewer becomes part of the system. Their auditory attention and footsteps influence the acoustics of the space. Yet while Boursier-Mougenot’s sound is organic and fluid, Zimoun’s is mechanical and highly precise. These are two poles of the sensory experience: organic vibration and mechanical noise.

Zimoun’s installations act upon the body as a physical environment — the vibration of air becomes tactile, creating a phantom sensation of sonic density. The body does not merely hear; it resonates.

Thus, the works discussed demonstrate how artists use light, smell, and sound as sensory triggers affecting the body without direct touch. Light alters the perception of space, turning the viewer into an element of the environment; smell activates memory and bodily associations, awakening emotional responses; sound creates an invisible architecture in which the body becomes a resonator.

What unites these methods is that they shift perception from the visual to the sensory. The viewer is no longer an observer — they are inside a system of perception, their body becoming an instrument of response.

In such environments, art ceases to be an object — it becomes a state lived through by the body. Light, smell, and sound form phantom forms of presence, returning to the body its capacity to feel even without touch.