Modernity in Focus: Alexander Rodchenko’s Photography

Table of Contents

1.Concept 2.Constructivist Perspective and Geometric Composition 3. Street Life and Worker Figures 4. Architecture and Spatial Rhythm 5. Portraits and Individual Representations 6. Industrial Aesthetics and Technological Imagery 7. Sport and the Movement of the Body 8.Conclusion

Concept

Following the October Revolution of 1917, the Soviet Union not only became an experiment in politics but also an enormous laboratory of culture. Artists, designers, and theorists all aimed to overturn the traditions of the pre-revolutionary past and create altogether novel aesthetic forms that would express socialism’s promises of dynamism, collectivization, and industrialization. Once seen as an inactive tool of record, photography was reconceptualized as an active force of ideology—capable of constituting perception, constructing social reality, and incarnating modernity in the proletarian state. It was in this climate that Alexander Rodchenko became a leading player, transforming the visual vocabulary of photography with his adventurous compositions, experimental perspectives, and adherence to Constructivist doctrine.

Rodchenko’s photography cannot be separated from the Soviet project of «building the new man.» His lens not only reflected the world but remade it. Welcoming extreme angles, overviews, diaganols, and broken frames, Rodchenko broke with the principles of classical perspective, and his work fell into line with the ideology of break and rebirth. These stylistic devices were not just novelties; they were means to an end. In Rodchenko’s vision, vision itself needed to be remade—liberated from bourgeois subjectivity and oriented toward the logic of mass production, efficacy, and technological lucidity. His images of staircases, fire escapes, balconies, and sports parades turned everyday Soviet space into symbols of discipline, motion, and collective power. This visual investigation into the interactions of form and ideology in early Soviet visuality employs the theory of Constructivism, and the writings of Arvatov and Gan in particular, to place Rodchenko among contemporaries like Dziga Vertov. Analyzing how his photographic aesthetic produced the grammar of modernity, the project conceives of Rodchenko’s camera as both visual apparatus and as social and political tool, a «new eye» for a new age.

By emphasizing Rodchenko’s characteristic visual methods—like the use of diagonal line, overhead perspective, and the modernist treatment of human subjects—this analysis reflects upon how photography was both an image of and an addition to Soviet modernity. Far from recording an achieved revolution, the work of Rodchenko imagines the very act of becoming: becoming modern, becoming industrial, becoming collective. In this manner, the work still challenges questions not just of art and propaganda, but of how we look, picture, and occupy the modern world.

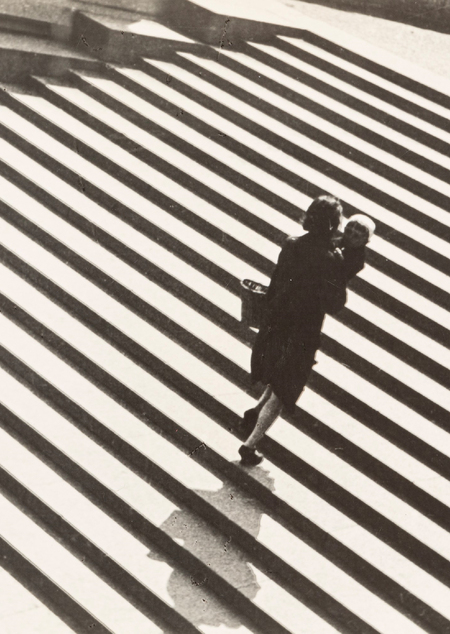

Constructivist Perspective and Geometric Composition

Rodchenko’s incorporation of extreme angles and geometric composition was more than just a visual preference—more a declaration of revolutionary vision. Inspired by the theory of Constructivism, Rodchenko’s diagonal and overhead compositions defied the passive stare of traditional photography, instead inviting the observer to enter an active, rearranged reality. These images defied passive looking and reflected the ambitions of the Soviets to restructure perception itself. The camera was used to retrain the eye to conform to the rational, mechanized pace of modern socialist existence.

Fire Escape (1925)

Power Station (1929)

Stairs (1929)

Guard on the Shukhov Tower (1929)

Mosselprom Building (1925)

Street Life and Worker Figures

Documenting the developing image of the Soviet citizen in the public space, Rodchenko’s street photography is anything but voyeuristic or romantic. These are photographs rooted in the logic of collectivisation and labor. Workers, traders, couriers, and city pedestrians are caught in motion, imbedded in the texture of Soviet quotidian. These portrayals focus on productivity, mobility, and the communal at the expense of the individual—a visual account of socialism in the making.

Cigarette Vendor, Pushkin Square (1928)

Courier Girl (1928)

Gathering for a Demonstration (1928)

Courtyard (1928)

Architecture and Spatial Rhythm

Rodchenko approached architecture not so much as a theme but as a language of modernity. By using rhythmic repetition, harsh contrasts, and upward-looking images, he converted buildings into visual metaphors for futurism, order, and social progress. His lens glorified the engineered landscape as the quintessential character of Soviet existence—where form existed in the service of ideology. The repeating patterns of balconies, glass buildings, and city infrastructures mirrored the new aesthetic hierarchy of the rationalized society.

Columns of the Museum of the Revolution (1926)

Glass and Light (1928)

Glass and Light II. (1928)

Curve of the Tramline (1932)

Ships at the Lock (1933)

Portraits and Individual Representations

Rodchenko’s portraits are strongly ideological. His portraits show people not in terms of internal psychology or feeling, but as expressions of the ideals of the Soviet state. As the subject is either a poet, worker, or member of a family, he is transformed into a representation of function, role, and membership in the collective endeavor. Rodchenko’s high-angle point of view, along with frontal composition, serves to stress the subject’s insertion in an overall social and political structure—yielding not personal narratives, but archetypes of the «New Soviet Person.»

Portrait of the Poet Vladimir Mayakovsky (1924)

Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (1924)

Pioneer Trumpeter (1930)

Girl with a Leica (1934)

Industrial Aesthetics and Technological Imagery

Rodchenko embraced technology and industry not only as topics but also as visual aesthetics. He approached gears, metal frames, factories, and machine minutiae with the same respect that was normally earned by traditional subjects. These photographs create a poetry of function: each component has a function, every detail is a service to the whole. According to this logic, the aesthetic of Soviet modernity is located in the machinery—its productive, ordered, efficient power made manifest.

Boats on the Moscow River (1926)

Gears (1929)

Lathe Machine Tools (1929)

Shuchov Transmission Tower (1929)

Orchestra at the White Sea Canal (1933)

Sport and the Movement of the Body

Rodchenko’s sports photographs are chromatic celebrations of discipline, wellness, and the collectivized body. Photographed either from above or at dynamic angle, they turn athletes and gymnasts alike into rhythmical patterns of motion. Rather than emphasizing individual excellence, they map choreographed unity—bodies moving in harmony with the other bodies around them, as well as with the ideology. These images visually affirm the Soviet ideals of physical culture as the driver of national vigor, unity, and vitality.

Marching column of the Dynamo Sports Club (1932)

Sportsmen on Red Square (1935)

Horse Race (1935)

Sports parade, Girl with towels (1935)

Male Pyramid (1936)

Conclusion

Alexander Rodchenko’s photographic practice is perhaps the most potent visual representation of early Soviet modernity. With the deployment of atypical viewpoints, plane geometry, and Constructivist composition, he provided images not of the novel Soviet world but also a radically new model for perceiving it. His camera functioned at the nexus of art, ideology, and technology—shaping visual culture in a rapidly transforming society.

By grouping Rodchenko’s photography according to conceptual themes—such as spatial construction and industry aesthetic, bodily habit, and street life—this study has shown how his photography reflected and helped to construct a socialist visual lexicon. Every photo was more than documentation; it was a piece of composition that involved political and cultural engagement. The factory, the body, the cityscape, and even the quotidian came to be refigured as symbols for progress and collective endeavor.

By emphasizing rhythm, order, and function, Rodchenko’s vision was in line with the utopian spirit of the Soviet avant-garde: that art had the potential to influence not only consciousness but reality itself. His camera was more than a machine—more a revolutionary tool. As such, Rodchenko’s photography is not only historically relevant but critically important, challenging us to rethink how images can embody and drive social change.

Today, looking back on the legacies of 20th-century modernities' visual vocabularies, Rodchenko’s body of work continues to raise questions regarding the function of aesthetics in the construction of political imagination. His photographs are not simply capturing a moment—instead, they create a future. And in so doing, they prompt us to reenvision the potential of vision itself.

https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/32894/fire-escape (Accessed 01/05)

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6195653 (Accessed 01/05)

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/56403 (Accessed 04/05)

https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/32898/house-of-mosselprom (Accessed 04/05)

https://middlebury.emuseum.com/objects/4056/courier-girl (Accessed 10/05)

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/4345/gathering-for-a-demonstration-alexander-rodchenko (Accessed 10/05)

https://www.artsy.net/artwork/alexander-rodchenko-the-courtyard (Accessed 12/05)

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/56397 (Accessed 12/05)

https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/276446 (Accessed 13/05)

https://www.artnet.com/artists/alexander- rodchenko/glass-and-light-jar-eAqMsL6rrAgBj2ftxBaOSw2 (Accessed 13/05)

https://www.moma.org/artists/4975-aleksandr-rodchenko (Accessed 15/05)

https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/32915/ships-in-the-lock (Accessed 15/05)

15.https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265183 (Accessed 16/05)

https://www.artsy.net/artwork/alexander-rodchenko-portrait-of-mother (Accessed 16/05)

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/83882 (Accessed 16/05)

https://emuseum.mfah.org/fr/objects/32903/boats-on-the-moscow-river (Accessed 16/05)

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6195653 (Accessed 16/05)

https://www.moma.org/artists/4975-aleksandr-rodchenko (Accessed 16/05)

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/10664/shuchov-transmission-tower-alexander-rodchenko (Accessed 16/05)

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/26505 (Accessed 17/05)

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4232946 (Accessed 17/05)

https://artblart.com/tag/alexander-rodchenko-sports-parade/ (Accessed 17/05)

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/106FZ2 (Accessed 17/05)

https://outflush37.rssing.com/chan-18803974/latest.php (Accessed 17/05)

https://www.nga.gov/artworks/130772-male-pyramid (Accessed 17/05)